One summer a decade or so ago, my mother, my daughter, and I took the old-school basic aluminum motorboat to Franklin Island, across from Snug Harbor but not so far as Regatta Bay. Soon after I was born, my parents sailed the sailboat they had built while I gestated to moor at Regatta Bay. The open water, the lap of waves against the hull, the seagulls, the primordial, once-were-mountains, and time-smoothed rock islands that change color with the sun and moon, these are all imprinted on my psyche. This part of Georgian Bay, Ontario, is, to me, more body-part than place. I breathe iron, murk, water, and stone.

That summer day with my mother and child, we enjoyed a small picnic of “No Frills,” the actual name of the grocery store in Parry Sound, bread, chees, and ginger ale. My daughter and I still call that beach on Franklin Island “Creepy Island,” although the entire island is not Creepy, the name has stuck. In the map of our shared experiences, what we experienced that day takes up more space than it should.

First, there were leeches, which we had never encountered before or since. I had to explain them to my daughter as one sealed its blood-sucking mouth upon her shin. We hadn’t brought a salt shaker so I had to pull it off by hand while it was alive. Strange arrangements of sticks and twigs stood among us. These were a couple of inches tall, insignificant in the immensity, yet all the same weirdly placed and present. Don’t misinterpret the beauty of our part of the Bay. Every other beach we have gone to does not have leeches or small sculptures. Just this one.

After our picnic, I lowered myself along the sloping streaks of rose-quartz and granite into the water since the place we would normally wade in was a leech kingdom. The way I have always done, from the place where water and rock meet, I dove forward. The Georgian Bay water is oxygen to me. All my pores breathe it. Everywhere else in the world suffocates me. I don’t notice it most of the time. Only when Georgian Bay reminds me. Rough and ancient, I feel at home there. All of it wraps me.

The water is perfect in July and August. I love to feel it from inside when I glide deeply, doing breaststroke below the surface. I got scolded one by a boat captain on Bimini. He’d taken me and eleven other tourists out to swim with wild dolphins. I had also gone the day before. I had forgotten to take the little GoPro camera in its waterproof casing. I might have gone a second day anyway after what I experienced the first. As soon as I’d jumped into the water, one or two of the dolphins encased me in a spiral like I was a cake on a spinning cake stand, and they were decorating me. It didn’t last very long, but experiences such as that, being swirlied by wild dolphins, punch a hole in time-space, keeping a part of you inside them forever. Still, I felt sad that I didn’t have my camera to capture it.

On the following day, I remembered it. I jumped in, obviously expecting a replay of dolphin attention. The dolphins were on a quest for something. I and the other tourists could see them steering past us. Craving an encounter, I descended and swam parallel to them. My enormous flippers did the trick. I wanted to swim alongside them for as long as I could. I swam farther than I thought. When I surfaced for breath, I heard the captain’s whistle, calling me back. If I wasn’t deaf, I might have heard him below the surface. I swam full-muscle back to the boat, leaving a quintessence of myself to carry on in its trajectory of dolphin life in the sea.

Gliding under the surface of Georgian Bay has always made me feel strong in the way we have to be strong to withstand the beauty of the natural world. You have to be a part of it and know its roughness is deeply personal. I don’t mean in an anthropomorphizing way, not personification either. Nature knows all there is to know. You have to become a part of that knowledge. Every single thing in and of and above and below is a part of nature’s speech. It is always making sentences, although the time between getting a human sentence out of an experience can vary between instantaneous and diuturnal. The latter is the case of the cormorant.

Intuition stopped my glide using my arms as brakes. I opened my eyes below the surface to see why I was stopped. I was face to dead face with a submerged cormorant. Its wings were perfectly outstretched measuring at least five-feet. They were interspersed feather and bone. Of the non-flying part of the body water and time had taken portions, sparing the general shape of the water bird. Its face was intact facing mine. Neither horror nor shock defined me. This was an encounter I knew would at some point find its way into my language. Between that moment and another moment I knew would come, the sight of the winged skeleton would haunt me as the thing I had to see, be shown, and make sense of. Every time the sight returns to me, I am more stricken by the thought I could have swum directly into and through it then surfaced covered in cormorant.

There have been countless such communiques, and now I can translate them into teachings regarding storytelling and healing. Inside us we have wings if bone and feather. We call it the parasympathetic nervous system with parts both seen and unseen, present and absent. It’s got receptors in every organ, prepared to heal the rest of us with subtle aerosols of nature’s love. In yoga, it’s called “the subtle system” and, more poetically, the Tree of Life. What clinical knowledge sees from one side, our souls see from the other and far transcends knowledge’s surface limit. It’s why we dream. The earth comes through eventually, if not in life then in death.

Hinduism, the origin of Buddhism and Taoism share the Tree of Life in teaching. A Bodhi tree in Buddhism reflects the sacred peach in Taoism. Both trees bestow immortality every two or three thousand years. Trees of Life appear in and grow from the Abrahamic faiths, all our problems, in fact, sprout from an issue regarding trees, one we can eat as much as we want, and one that we need to avoid.

Cormorant wisdom has led me to see the former as the Tree of Storytelling and the latter the Tree of Thinking without the heart— outside the parasympathetic system. This system, the body part that heals us with its words, is the subject of ancient texts. Words that don’t fly forth from its feather and bone are spoken in vanity and only deepen our suffering and cruelty.

But the texts are not our only reminders. The trees in winter remind us, as well, of the willowy, healing vines inside all of us, the tree of consciousness and story. A peacock’s tail share the tale, too. Angel imagery of great wings suspends human form in air. Birds, in general, remind us. Levity we find in laughter reminds us. Love reminds us. In profound and direct encounters with wilderness, even clouds, we see our magical aspect reflected back into us, mirrors of the hidden healing system inside us, the storyteller beyond and within the body, the receiver of nature’s voice that must use objects and living things to spell out our purpose. All of this real.

I don’t think I told anyone about the cormorant. It was too striking, too strong a hit off the pipe of the primordial order. Creepy Island was already creepy enough. If I had told my then-still-a-child daughter, she might never have gone in the water—or even to our cottage— again. Instead, I have kept it inside me, as we say of stories that weigh us down and sicken us until we tell, forgetting again and again that only when we tell, does that great waterbird within us come alive.In Genesis, God tells Adam to name things so that we can call things by their names.

It’s important that we do this, for when our words and the things and concepts they signify conflict, peace and harmony can’t happen. It is in this spirit that I, a storyteller, decided to cross into the medical field for a decade to track the conversation and data around a then-emerging discipline called Narrative Medicine. We creative types have long accepted that creativity won’t make more than a handful of us rich. We have accepted that people call any idea we have “woo woo.” We have even accepted that we will never be taken as seriously as someone who wears a lab coat. We who can read nature and listen to its infinite languages inhabit an entirely different reality which to us is more real.

We are the hangers-on to something powerful and wondrous because we cannot imagine life without it. We attend to our craft of naming things by their names. We are the scribes of the species. We carry the weight of what our counterparts do in the name of science, technology, money, and power, and we transform it into storytelling in its various archaic forms. Our culture calls our work “Arts and Entertainment.” We call it medicine. We have always called it medicine.

We are the macro version of The Storytelling System in the body. We watch, We wait. We heal. We come forth from our shadows to mend that which has been broken, be it trust, be it the heart. We are sensitive, mostly quiet unless surrounded by kindred. Get us in a storytelling circle with friends, and we are not quiet at all. To the outsiders ensconced in the material world, we’re weird, and we’re okay with that.

The Storytelling System appears in images as a diaphanous cloak the body from within, a woolen cormorant. It is a shroud of care we enfold in when life has thrown us. We are received by it. It welcomes us and assures us that whatever happened was awful, and we are not over-reacting. It is a judgment-free space where we are free to allow our thoughts to be jumbled, and free to take our time meandering through them. In this space, we will reflect, something we don’t have time or skill for doing in the high-speed sympathetic system always on alert. Here there are no alerts. Just time and breath, and after a while words.

Maybe you can see why it is so vital that I speak up about what we ought to call this system. Stories don’t show up on brain scans. They don’t show up in measurement. Science sees science. That is, until science recently discovered that stories heal us. Stories release oxytocin that reduces inflammation. Stories lower pain scale reports and blood pressure. People who join poetry-writing groups with zero pressure of critique often no longer need painkillers and anti-depressants. Hospitalized children are happier when storytellers are telling. Storytelling ends loneliness. See why I had to step in?

We are talking about our humanity, about a part of the body that keeps it safe. More than that, it renews us entirely so that we can enjoy life right up until it’s time to slough off our mortal flesh and move on to where our imagination leads us in the interim. Storytelling is how the Tibetan Book of the Dead says we transmigrate. When we are talking about the Storytelling System, we are talking about the universally held and agreed-upon nature of being human. If we want to be healthy and happy we have to create every second of our existence.

Reality is a starting point. It’s what we do with it that counts. If we are reactive and uptight chances are we will stay that way because life won’t change. It doesn’t settle down. We have to be the ones to settle down and alter our perception using our story.

Mindfulness teaches us that we can step out of the fray at any moment and recharge and renew, but there are dimensions of mindfulness that are very hard to imagine–mainly because we can only move through these dimensions and their thresholds with imagination. Until we are speaking or writing from within our stories, we can pretend that reality is the real order. This is why we have needed sacred texts and practices. Without these, we would not know we have a bodily system for healing. That is, unless science found it and wrote a thousand websites praising its functions and benefits–not the least of which is that it transforms us into competely different people.

Completely different people who feel they have enough food and money, have enough friends, have reached a goal and don’t need to go after another goal, have enough. People who have enough don’t need to go after somebody else’s stuff. They don’t hate anybody because when you feel calm and relaxed you enjoy the company, whoever it is. You’re completely satisfied sitting on a plot of green grass on a Spring day under a beautiful tree. Completely different people are compassionate.

The purpose of the Enlightenment was to find the Divine through Science. It succeeded and led us to Storytelling. Narrative Medicine data citing storytelling’s curative powers can’t explain the “how.” Creativity washes us in oxytocin which reduces inflammation throughout. And we can produce our own forever and no longer want. Nature’s medicine.

In Hinduism, the root of Buddhism and Taoism, the Tree of Life is the symbol of the parasympathetic nervous system. It is attained through yoga practice. This Tree appears in our lives and stories so we remember to breathe lest we get swept up in the illusory world. When we breathe, we return to our trees, as a Welsh saying describes. When we breathe, we connect to the earth while gaining perspective and insight into all the challenges. From within the earth, we transform sense into myth, the deeper world.

Druids and their healing counterparts in the world’s cultures traveled the world teaching and healing, and sharing wisdom. This map displays The Sword of Michael is a direct geographical line connecting seven sacred sites. Skellig Michael, the craggy rock natural pyramid topped with beehive huts in County Kerry rests at one end and Stella Maris Monastery on Mount Carmel, Haifa. Sarcen, the term for the enormous stones that form Stonehenge and other Stone Circles, means “foreign” and derives from “Saracen,” the term for people of the Levant. Naturally, church history explains it all from the western perspective. What the line means and meant to our non-westernized story-practitioners hs yet to be known after three centuries of paralyzed imagination.

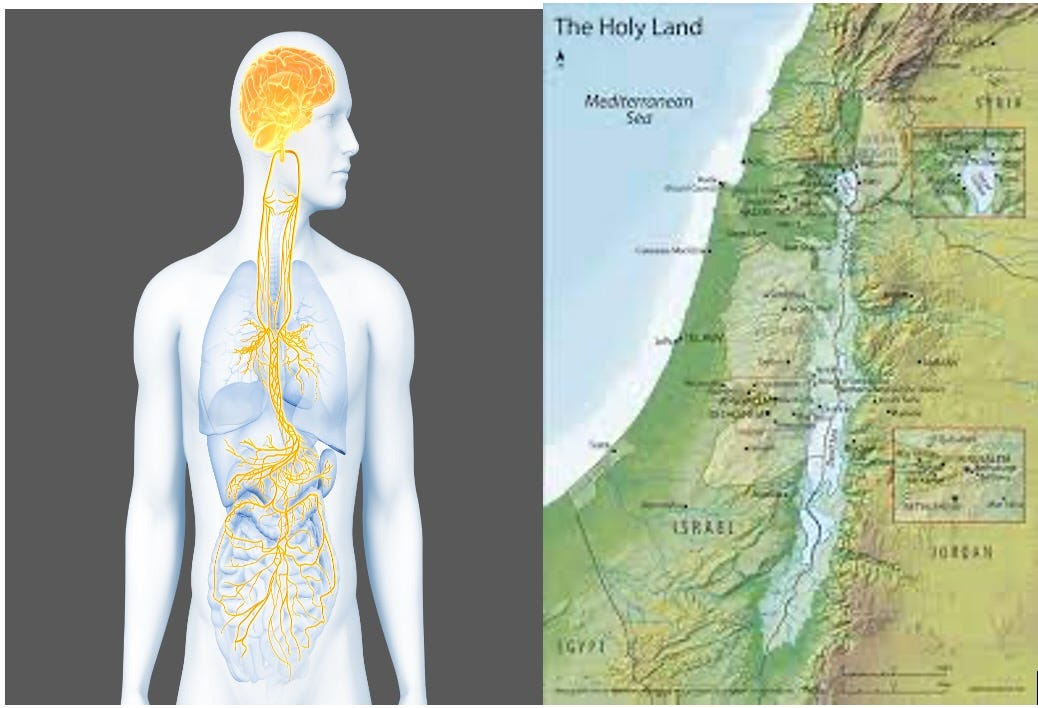

On the left, the Parasympathetic Nervous System, seat of creativity and healing. On the right, a place with many names in three ancient Books that tell us to look within, to transform suffering into creativity, and to with sword and fire rid ourselves of outmoded thinking. Everyone is right. No need for war of hate. We have an invisible “System.” It’s for healing with stories– in the Indigenous Tradition from which we all descend and which is more powerful than we can conceive.

Completely different people have peace and want to share it. This is why the sacred texts and practices lead us there. It’s the promised land. It even looks like the promised land, and there’s the greatest wonder of all. All the war over The Holy Land is for nothing. It’s a metaphor for what’s inside us. Within. As reflections of the earth, as above so below, we humans are geoglyphs, bound to it with love.

I’ve looked at countless maps of body and land. I have told my story and been healed. It stands. Our ancestors were geniuses who knew everything. It took us a while. We made it back. Or are starting to. We see currently in the merged fields comprising Narrative Medicine an evolution of frameworks.

A Pedagogy of Suffering is evolving across education, medicine, and sociology (and probably more) “a pedagogy that turns away from suffering suffers a great loss, and how a pedagogy that turns towards sufferingcan become a locale of great teaching and learning, great wisdom and grace.” In the Fibonacci sequence of systems-change, The Wounded Storyteller by sociologist, Dr. Arthur Frank builds upon The Illness Narratives of Psychiatrst and Anthropologist, Dr. Arthur Kleinman. Dr. Rita Charon’s Narrative Medicine: Honoring the Stories of Illness builds upon both, and so on. The sciences may have been taught that knowledge can only be gained by five-sense experiments and pure reason only attained through scientific thought, but the knowledge we gain through storytelling turns out to be the more reliable method. This is because storytelling is the tree of life. Our tales of experience graft us onto our primordial selves, unifying us with greater story, our universe’s mythic adventure.

Ways the scripture teach us how to graft ourselves back into reality include:

Let the words of my mouth and the meditations of my heart: creativity

We shall know them by their works: creativity

Sing to the Lord a new song: creativity

Don’t put old wine in new casks: be very creative

A coat of many colors: the parasympathetic system

The Holy Ghost, i.e. entire body system for story healing that grafts us upon the greater Story of the universe. . .

Exodus from the ego/intellect/emotional limitations into Self/imagination/intuition freedom of Mind

Expulsion: Childhood-Adult development

Lot’s Wife: Once you’ve made the crossing, leave a lot behind

Noah: it’s not an easy journey, bring your animal self, your heart

Song of Songs: be passionate, love, enjoy your body and soul

Paul in prison: Paul in this mess

The Thunder Brothers: join a band

Turning white and shimerring: Being in the parasympathetic is a disco that never ends

Confess and repent: Tell your story, you’ll heal; tell all your stories, you’ll be transformed and stay in the parasympathetic

Walk by faith, not by sight: Trust me, there’s a whole other body system that the ancestors knew thousands of years before we did.

Through a glass darkly: we only “see” and “hear” it in creativity after childhood ends

The order of Melchisidek: creative alchemy is the path, and we can get there on our own

Number of the beastie: mindless, meaningless repetition is the devil

In short, we can stop taking ourselves so damn seriously. Yes, there is a path to wisdom. Yes, we all are on it and need only develop it by telling our stories. Storytelling is the only serious thing, yet in the West we have been taught anything except storytelling is serious. The stories themselves are joyful and life-renewing, even the hard stories of things we survives, as we and they reflectively change over time. If we are not taught this, we will never know the meaning of life and will instead make jokes about it.

By naming the Parasympathetic Nervous System The Storytelling System, or The Tree of Storytelling, we aren’t hiding it anymore. It has been hidden in mystery for too long. We have it. It’s real. It’s inside us, and every spiritual practice and scientific experiment regarding storytelling and healing lead directly to it. They lead to Peace.

Understandably, it is a challenging concept for a culture engineered to value science over storytelling. To help anyone still wanting science, here is The Polyvagal Institute.